|

|

Post by Fenril on Feb 7, 2017 0:23:26 GMT -5

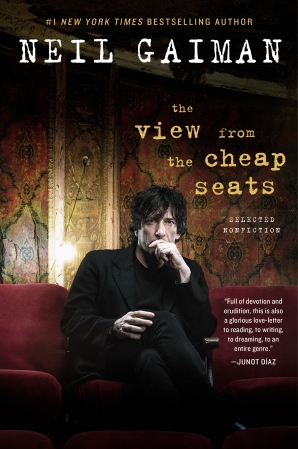

- The view from the cheap seats. Neil Gaiman. A collection of nonfiction from Neil Gaiman; includes essays, speeches, articles, interviews, introductions for assorted books and much more. Arranged not in chronological order, but by theme; covers a wide variety of subjects and people, all deeply connected both to Gaiman himself and to his multimedia oeuvre.

After reading the introduction, which encourages us to read this book in whatever order we please, I decided to navigate it in much the same way I like to explore places I travel to: First the spots (here, the pieces) that catch my eye or that I wanted to visit (read) from the beginning. And then, tracing my way back from the end to the beginning, to cover all I might have missed. Sometimes revisiting stuff that I really enjoyed or that I wasn’t sure I quite understood the first time around.

And the journey is rewarding —so many wonders, so much food for thoughts. There are occasional missteps —a rather failed report of London at night, for instance. There are ideas you might not agree with —the piece about books having a particular gender is, no doubt, sincere; it’s really not a notion I’ve ever felt as a reader or as a writer, however. But even those pieces have something worth reading, ideas worth pondering about. And the best pieces, well!

Gaiman’s career up to his point has had high and lows. In comics, “The sandman” remain his best work (with quite a few other jewels worth discovering along the way). In prose, I always found his novel “American Gods” rather uneven, but loved his short story collections and the novel “Good Omens”, written in collaboration with Terry Pratchett. In movies, “Mirrormask” and “Coraline” are classics in their own right. And in non-fiction prose? He’s ambitious, and often in a way that makes it seem like he’s not. All pieces come across as both sincere and amiable; all reveal a carefully planned structure (even a particularly humorous “introduction” for a book he claims to have never actually read). Some pieces are sentimental (be they about love, about sorrow or about anger), some are erudite (but not pedantic), some are whimsical and quite a few are passionate pleas for reading and for open-mindedness. It’s hard for me to choose a particular favorite, though his essay on the dreamlike quality of “Bride of Frankenstein” probably comes close (Oh! But what about the pieces on Lou Reed? Or the assorted pieces about myth and fairytales? Or the speech about the importance of libraries? Or, or…).

All in all, very recommended.

|

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Feb 20, 2017 21:43:02 GMT -5

- Mockingjay (The hunger games, vol. 3). Suzanne Collins. After surviving not one but two death games, Katniss Everdeen is close to exhaustion —physical, mental and emotional. Which is too bad, because revolution is finally on the way, courtesy of the legendary District 13. And its' leaders want Katniss to be their symbol: A Mockingjay to inspire people, to make them stand united in opposition to the Capitol. Having seen the horrors of war far too often and far too close, she has no interest in playing any role for any group. Unfortunately, she does not really have a choice anymore. For her loved ones, her allies, and essentially everyone she’s ever known are all in grave danger. After all, war forgives no one, and makes no distinction between victims… Third and final installment of the infamous “Hunger Games” trilogy. By this point the story has evolved from dystopian yarn to war drama / political thriller. There are parts of the book that seem to have been included solely as crowd-pleasers (the many lethal sci-fi traps that the Capitol employs, the focus on a romantic triangle of sorts and of course, the mandatory epilogue with our survivors happily married and raising children of their own), often to the detriment of the previous novels. Yet there is also a bitter undercurrent that heavily criticizes not just the very concept of war, but the ease with which the general populace tends to let itself be manipulated by media and the way many victimized groups are sometimes used as arguments in political debates that amount to little more than a tug-of-war between power-hungry leaders. In other words, this final installment has both the best and the worst elements of the entire Hunger Games story. Overall it’s a satisfying enough ending, but it’s hard not to feel that this is one of those books that did not need to be stretched into a series. Really the first book was enough. |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Feb 20, 2017 22:32:10 GMT -5

- The Invasion (Animorphs, vol. 1). K. A. Applegate. Jake, Marco, Tobias, Rachel and Cassie. Five ordinary junior high kids who were walking back home from the mall one night when suddenly they run into something quite extraordinary: A dying alien. Who informs them that Earth is already under a massive invasion. As a last-ditch effort, said alien grants the kids a unique power: That of morphing into any animal they have ever touched. It is a wonderful, dangerous, and borderline addictive power. Which they will have to take as much advantage of as they can: For their enemies are nothing less than lethal. And they are already far closer than anybody would like… The book that launched one of the most successful children’s book series of the 90’s (at the time, on par with “Goosebumps”, though this one was never adapted to another media, to the best of my knowledge). The plot would seem typical 80’s / 90’s fare (diverse group of youngsters receives super-powers and must defend their town from a monstrous enemy); and to tell the truth it is, although this one really emphasizes just how scary such a situation would be (lots of body horror and psychological trauma going around here). Worth revisiting. Also, dig that other hallmark of 80's / 90's paperbacks: The stepback cover! |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Feb 27, 2017 21:09:03 GMT -5

Reading Challenge, February: Read only YA and children’s books, in Spanish, English or Italian. - Charlie and the chocolate factory. Roald Dahl.  Charlie Bucket, perpetually starved and living in a barrack of a house with his parents and with both sets of grandparents, is nevertheless an optimistic and good-natured child. One day, he becomes one of only five winners of a contest. The reward: A tour of Willy Wonka’s mysterious chocolate factory, followed by a lifetime supply of chocolate and candy. The catch: There is a reason this factory is so mysterious and closed to the public. More than a factory of sweets, it is quite literally a place of dreams. Also a place of nightmares for certain children. Like the other four winners of the contest, who are not exactly as good-natured as Charlie… Classic book for children and something of a modern fairytale —with all the sense of wonder and the cruel twists of fate that entails. Adapted twice to cinema; neither movie quite captures the playful yet subtly sardonic tone of the original book. Is it judgmental and debatable, particularly as regards the portrayal of the other four children and their parents? Sure, but that is part of what makes the story a fairytale —good, evil and even neutral characters are all exaggerated and larger than life. Overall it retains the necessary charm even now. Quentin Blake’s illustrations are a delight, and a good companion to this deceptively simple tale. |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Mar 6, 2017 21:56:05 GMT -5

Reading challenge, March: Read only comic books.  - Clean Room, vol. 1. Gail Simone, et al. After a botched suicide attempt, intrepid reporter Chloe Pierce gets back on her feet, determined to solve the mystery behind her husband’s suicide. Chloe’s investigations lead her to worldwide celebrity Astrid Mueller, failed novelist turned self-help guru. But there is more to Mueller’s “Honest World Foundation” than just a trendy cult. It seems Mueller has been tapping into very dangerous forces quite outside most human experiences. And soon, Chloe finds herself accosted not just by her personal demons, but by an all-too-real kind of relentless supernatural menace… A very strange and quite horrific tale that deftly mixes several trendy topics (celebrity cults, paranoid conspiracies, modern sexuality) with visceral gore and a complex mystery at heart. Peopled with memorable characters (especially the women, both intriguing and deadly) and peppered with witty dialogues. It demands both attention and patience from the reader, as the central mystery has no easy answers. Overall quite recommended, both for fans of Simone and for horror fans in general. |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Mar 6, 2017 21:59:48 GMT -5

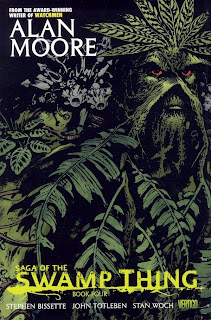

Reading challenge, March: Read only comic books.  - Saga of the swamp thing, vol. 3. Alan Moore, et al. The third volume of Moore’s seminal run on “Swamp Thing” introduces the infamous John Constantine and kicks off a genuine “American Gothic” arc. Here, Swamp Thing and his allies tangle with several unique American haunts —a toxic derelict aptly nicknamed “Nukeface”, a coven of underwater vampires, a woman’s revenge against oppressive patriarchy with the help of the moon and an ageless curse, and a plantation haunted by the ghosts of both slaves and captors. Very much recommended. |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Mar 13, 2017 18:52:46 GMT -5

- Saga of the swamp thing, vol. 4. Alan Moore et al. Fourth volume of Alan Moore’s seminal run on “Swamp Thing”. This volume continues and concludes the “American Gothic” arc, once again dealing with uniquely American (USian) monsters —the mandatory serial killer given a nicely ironic punishment; a riff on the infamous Winchester house. Not surprisingly, this last yarn earned the ire of quite a few readers for daring to criticize US’s obsession with guns. Ahem. After that, an event that is both crossover of sorts with the general DC Universe (cameos by several iconic characters, a direct tie-in to the infamous “Crisis on Infinite Earths” event) and the crescendo of the “American Gothic” arc. Here it crosses to South American territory, which merits a particular comment: Moore got Chilean mythology mostly right, which is rare and appreciated. He also portrays both Chile and Brazil with a rather colonialist perspective. Yet another European / USian yarn in which most of America is basically just this huge jungle for our (preferably white) heroes to have adventures in. This part is not appreciated at all. The result, however, is remarkable: An epic “good vs evil” fight that quickly manages to deny both sides and propose a notion that, as Neil Gaiman writes in his introduction, some religions (he says “most”, which is inaccurate) would find heretic. That good and evil NEED each other. Along the way (this is another note from Gaiman, this time an accurate one) there is a subplot that manages to pinpoint the very close links that voyeurism and puritanism share —setting up a story for the next volume. All in all, recommended, but by this point only as part of the series rather than by itself. |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Mar 13, 2017 19:00:34 GMT -5

- In clothes called fat. Moyoco Anno. Noko has a good job, a fine social life and a loving boyfriend… on the surface. Her profound insecurities about her body (she is overweight) have inadvertently made her a target of frequent manipulation and bullying —from a vicious co-worker, from her boyfriend, from other ostensibly good people she runs into… Soon Noko embarks on a quest to lose as much weight as fast as she can, believing that changing her body will finally bring her happiness. She is about to discover just how cruel the world can truly be. An amazing, brutally sincere and unflinching comic from one of the lead “Josei” manga artists. The psychological insight and social critique are nothing less than remarkable. There is some discussion about whether this story should be taken as a dark (very, very dark) comedy of manners or as an intimate psychological drama. This is a story in which no character comes off good: Noko herself is done in mostly by her lack of self-esteem, and all the other characters range from monstrous to petty people who believe themselves good. Perhaps it’s possible to read this story as a plea for sympathy. Had any of the people in it been more wiling to listen to each other, things might not have ended as badly. (And then again, they might: Not unlike in real life, the characters frequently blame others for their own flaws and failures). Beyond such considerations, what we have is an honest and powerful yarn more than worth reading. Recommended. |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Mar 13, 2017 19:08:54 GMT -5

- Tropic of the sea. Satoshi Kon. For centuries, the Yashiro family has kept an odd tradition: Every sixty years they are entrusted with a mermaid egg that they must return at sea when it’s ready to hatch. In exchange for this favor, the coastal town they live in is blessed with bountiful fish and calm seas. But times change, and right now the current head of the family intends to bring in modernity —new buildings, new hospitals, and the egg being repurposed as a tourist attraction. His son, Yosuke, finds himself torn between tradition and prosperity. As fights erupt in town over this conflict, he increasingly wanders to the sea seeking for an answer. It might come at the hands of a creature with an enormous fin he’s just witnessed. Or maybe in the wake of a major disaster on the way… Though far more famous as an anime director, Kon was also a remarkable manga artist. This, his first collected work, is a poignant environmentalist story that is remarkable both for the folklore and for the social analysis contained within. Recommended. |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Mar 20, 2017 14:01:12 GMT -5

- Saga of the swamp thing, vol. 5. Alan Moore et al. Fifth and penultimate volume of Moore’s seminal run on “Swamp Thing”. This can be read as a transition volume —from the initial horror-tinged run (and during it, from American Gothic to outright cosmic horror) to a more science-fantasy (as opposed to just sci-fi) atmosphere. There are two stories here of particular interest… three, rather. There is “The garden of earthly delights”, what you could call vintage Moore: All the horrors and delights of his best works in a single, delirious yarn. There is “My blue heaven”, the exact point where the horror to science-fantasy transition takes place, and an elaborate metaphor about the artist who has finished one work, has finished winding down and is now ready to embrace his next creation. By itself it is also a haunting, atmospheric tale of madness. And then there is my personal favorite, “The flowers of romance”, in which we revisit two old cast members who had been discarded early in the run (in the very first issue of the very first volume in fact) —and we run into an intensely horrific tale having to do with crazed survivalists and deeply scarring spousal abuse. We also see the evolution of Abby Cable, from supporting cast member, to love interest to a powerful character in her own right. That this story was based on a real-life anecdote from Moore’s family (and it’s every bit as horrid in context) makes Abby’s triumph that much more satisfying. And that this story was written in a burst of inspiration between arcs (it’s the only one that wasn’t planned from the start) probably explains how dynamic and, for lack of a better word, fresh it feels. |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Mar 20, 2017 14:07:24 GMT -5

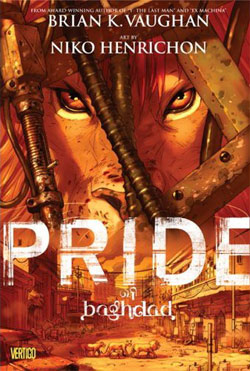

- Pride of Baghdad. Brian K. Vaughan, et al. A pride composed of four lions (one male, two females and a cub) find the Baghdad Zoo they live in destroyed during an American bombing raid. Now the freedom they have desired for so long is within grasp! But the problem with freedom resulting from an accident is that there is no organization. Where to go, what to do? And then, is the world of humans really any less dangerous than the wilderness they remember? Loosely drawn from a real-life case, this graphic novel tells an interesting yarn that also intends to pose questions regarding the nature of freedom. It’s not entirely successful in this last respect, due to a certain bias from the writing toward the notion that freedom is something to earn and not a given right. That writer Vaughan thanks both the civilian population of Iraq and the US Army in the epilogue explains the basic problem: a lack of understanding that masquerades itself as sympathy. It is quite true that growing up under an oppressive regime but as a privileged element deprives an individual of the necessary skills for survival (for the analogy, look no further than the lion raised as a pet who easily starves once the human masters are gone), but stating that people in such a situation will never rise on their own and must absolutely be saved by outside forces (and gradually) is hard to take as anything but a naive, simplistic viewpoint. What of this story without the political intention and simply seen as a tale of four animals trying to survive in a world they do not understand? Ah but the problem is that this story never lets you forget that all the talking animals featured here are meant to represent humans. Not humanized, which pretty much any story requires, but literally human: The lioness with a scarred eye resulting from a gang rape incident, the turtle who watched his family drowning in petrol, the doomsayer bird, the cultish monkeys, the racist / spiciest gazelle, the bear who fancies himself a king… none of these can be read as anything but humans in an animal skin, as opposed to animals that represent human characteristics. Is this, then, a bad comic? I would say it’s failed rather than bad per se. There are plenty of interesting ideas, stunning landscapes and other sights to behold, and even a nice handling of character development. Watching Zill go from coward to reluctant leader and decisive fighter has plenty of merit, for example. It’s just that this comic wears it’s intention on the sleeve and does not quite achieve what it intends to do. Even so, it’s worth a look. |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Mar 27, 2017 22:40:51 GMT -5

- Saga of the swamp thing, vol. 6. Alan Moore et al. Final volume of Alan Moore’s lauded run on “Swamp Thing”. Having successfully shifted from horror to science fantasy in previous volumes, this one more or less brings back previous threads (literally and figuratively) with a new perspective. There are those reinterpretations of old comic book characters that Moore would become famous for, and that quite a few people have seen sought to imitate, both successfully and not. Here, it’s Adam Strange (“Mysteries in Space”), Thanagar the world of the hawkpepople (“Exiles”) and especially Green Lantern Medphyll (“All flesh is grass”). All of them are given a certain sexual undercurrent, as is characteristic of this particular run of “Swamp Thing”. With Strange and the hawks, mostly violent. Strange himself comes across as something of meathead —perhaps due to frequent lack of satisfaction… or perhaps simply because he’s a perennial fish out of water. As for the hawks, the fetishistic elements of their outfits and methods is made more explicit than usual. Ah, but the real highlight of these is Medphyll. A uniquely comic-book concept (a superhero from a planet of sentient plants) is given an expansion and reinvention here —witness the wonders of a world where vegetables are the intelligent life form and all other organic beings the lower. Thus, there are chemical restaurants, pet shrubs (“Finely bred but quite unintelligent"), young women urged to be modest and mask the scent of their flowers —and older women “heavy with fruit”, venerable trees who only eat animals and never other vegetables… But here, too, there are all too human dramas: The lovers drawn apart by too much need of each other; the fastidious artist who wishes to be left alone by her fans —only to discover just how alone she truly is, how empty her soul feels without companions; the suicidal priest who has lost his faith but regains it in the middle of a catastrophe. And then there is Medphyll himself, an old and wise hero (very much what the Adam Strange of this version should aspire to be) here mourning his mentor Jothra. And there is a very strong implication that the relationship between the two men wasn’t just that of teacher and student, that it was romantic in nature. And in the midst of this there is a story of pure “science horror” (scary sci-fi? It’s unquestionable that such a thing exists, but I don’t think I have ever seen an exact name for this genre or sub-genre), “Loving the alien”. Closer in spirit to quite a few European comics than to mainstream US productions, hallucinatory and utterly horrific. I personally liked “All flesh is grass” better, but this story is still a highlight. There are two fill-in issues here. “Reunion”, from Stephen Bissette, is more or less a callback to the early horror issues of this run. “Wavelenght”, from Rick Veitch, is a somewhat formulaic adventure story featuring iconic characters Metron (never more annoying) and Darkseid; it gets bonus points for being an explicit homage to Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges and for the amusing moment that is Darkseid calling Metron an academic chicken. Neither story quite matches the quality of Moore’s, but they are good yarns on their own. And then there is the conclusion, which successfully closes all ongoing threads except for one (what did happen to Nukeface? I mean, no doubt there is an answer somewhere on the internet, but I would have liked an answer right on the book itself) and has our cast members reach an epiphany about the nature of mankind and of the world itself. Can’t say I share Bissette’s reading of this conclusion as “Bittersweet”, though. Personally I found it quite sweet and appropriate. More so considering at what point in Moore’s career this was written… Conclusion: LOVED the entire run, definitely a must for Moore’s fans. |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Apr 3, 2017 20:38:14 GMT -5

- A small killing. Alan Moore & Oscar Zárate. Self-absorbed ad designer Timothy has accepted the opportunity of a lifetime: A cushy job working for Flite, the #1 cola company! But of late he’s been plagued by something disturbing —a demonic child who keeps showing up in the most unlikely places and who, when confronted, outright admits that he wants to kill Timothy. But why? The 80’s were in many ways Moore’s golden age as a comic book writer. Having completed several now-legendary assignments (his runs on “Swamp Thing” and “Miracleman”, plus the infamous “Watchmen” and several more), here was yet another important transition: His first major work that had nothing to do with superheroes. Joined by the equally extraordinary Zárate, the duo crafted an intense exploration of a complex yet quite ordinary character. For in many ways Timothy really is us. His increasingly desperate monologues take us from that boredom with everyday life, that ennui we have all felt now and then, to those little lies we tell ourselves whenever reminiscing about the past (and which, upon closer inspection, are revealed not to be quite as little as we think) —and then all the way to the origin of evil. But individual, strictly personal evil. And from then, a necessary battle for the soul, literal or metaphorical… A somewhat overlooked gem from an extraordinary pair of artists, not to be missed. |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Apr 3, 2017 20:46:49 GMT -5

- Fashion Beast. Alan Moore, Malcolm McLaren, et. al. Doll has just been fired from her job —she was the coat checker at a trendy club until an enraged customer messed things up big time. As fate would have it, that very night she landed herself a spot auditioning for haute couture mogul Celestine —and was personally chosen to be his new model! But there is so much below the glamour, so much spite and madness and darkness. Yet there is also beauty, intriguing mysteries and even love —but from people nobody could have expected. Here is a rarity of rarities. First, instead of yet another comic book adapted to a movie, witness the comic book adaptation of a long story originally meant for the screen. Second, witness the result of the meeting between two remarkable minds of the twentieth century —writer Alan Moore and multimedia artist Malcolm McLaren. Third, it’s a twenty-first century adaptation… no, resurrection, of a project meant for the 1980’s, and yet it’s very much a fable for our times. And lastly, care to read “Beauty and the beast (but by way of Jean Cocteau) meets Phantom of the Opera (or perhaps “Phantom of the paradise” might be a better smile) meets queer romance meets fashion-as-metaphor-for-art-and-obsession (of all things in the world, a point in common with the anime “Kill la kill” —not the endless fan service, but the subtler theme of clothes as metaphor for ideologies. Not because the respective creators have anything to do with each other. Rather, because it’s shaping up to be a topic very much of these times) meets psychedelic comics”? Behind all the novelty what we have is still a remarkable comic. And a very strange, very unique one. Speaking from personal experience —I have been on an Alan Moore kick of late, re-reading many of his most and less popular oeuvres. It seems fitting to me that this last one (for now) is one of the hardest to classify. Subtle fantasy or high satire? Or, honestly, so many other possible interpretations. The best recommendation I can give is this: No matter what you are expecting, this comic will surprise you. It is as challenging, delightful and ultimately rewarding as just about anything else you have read from Moore. Quite recommended. |

|

|

|

Post by Fenril on Apr 13, 2017 23:09:08 GMT -5

Reading challenge, April: Read only scripts (stage plays, screen plays, tele plays, etc.).  - Rent. Jonathan Larson. A community of young bohemian artists struggle to make ends meet —and with the arrival of a mysterious, deadly disease: AIDS. But this is not a cautionary tale. Instead, it is a life-affirming and -celebrating odyssey about the kind of human spirit that refuses to break even under the harshest kind of duress. However hard life can rend you to pieces, there is still “no day but today!” as one of the most memorable songs reminds us. Poignant rock musical that was Larson’s magnum opus and, sadly, his last play. Relevant both within it’s historical context and without. |

|