Post by 42ndstreetfreak on Nov 29, 2005 8:46:44 GMT -5

Come and See (1985)

Dir: Elem Klimov

Russia, World War II.

A young boy, Florya (Aleksei Kravchenko) joins the local partisan group and thinks he is about to start on a great adventure and save his country from the Nazi invaders.

The reality is very different. The reality is failure, hunger, mud, cold and despair.

The reality is death from afar, death up close and personal, death by laughing, sadistic, swarming hordes, death with no hope of retaliation, death with no end.

The reality is simply…death.

And for Florya death becomes an agonising metamorphosis as everything he was is destroyed, to be replaced with the now stinking, burnt earth of Mother Russia….

Made to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany, the late Elem Klimov’s “Come and See” is perhaps the single most harrowing, bleak and frighteningly realistic portrayal of the true barbarity of all out warfare ever put on screen.

It makes the stupefying dull and self consciously worthy “Schindler’s List” look like the dinner party conversation piece it really is.

Shooting with a jagged, documentary like energy (that never, it must be pointed out, goes into the brain spinning chaos that has become so popular recently) Klimov effortlessly moves us from small scale, intimate moments to extras packed, large scale chaos as he documents the tragic true life events that his fictiona protagonist will lead us through.

Just like the young character we follow, we are never sure just what we are about to come upon, what we are about to witness and how small, large, unimportant or pivotal it may be.

And when added to the stunningly authentic props, costumes and the visual detailing of scenes, we are truly taken on a journey that comes as close to reality as any of us would ever want to get.

Even from the organised chaos of the initial partisan hide-out in the woods, where Florya’s journey truly starts, the young lad is instantly thrown in at the deep end when put on, a very nervous, guard duty.

And not even when he meets a pretty young girl in the camp, Glasha (Olga Mironova), are things as they should be.

Glasha, despite her youth, is obviously already a veteran of the terrible lifestyle the partisans lead and in a wonderful sequence Florya is shocked to discover how close to the surface true madness and black despair lie in the young woman.

He glimpses his future and he does not realise it.

A vicious bombing hurls both the youngsters into the real horror and Florya is soon to witness ever increasing levels of loss and murderous barbarity. Every new horror rips away more and more of the naivety that shielded him from the truth when he first volunteered.

With Glasha leading him (after he is partly deafened by the bomb blasts) Florya does find a brief childlike haven from the horrors as the strange girl dances in the rain for him and together they feel just that bit less vulnerable.

But war is no respecter of respite and Florya will be thrown back into a bedlam worse than he could ever have imagined when they make a return visit to his home village.

And in a gruelling (really gruelling for the two young actors that’s for sure), slow motion sequence we are witness to a manic, despairing Florya tear them both through a filthy, sucking bog as he tries to escape from the truth he cannot face. And we can almost see the child in Florya peeled off layer by layer with each slurping grasp of the stinking mud.

And when a now much hardened Florya (though still hopeful of some kind of victory) sets out with three other partisans to get food he is separated from Glasha and truly plunges head first into a literally soul shredding, mind destroying, inferno.

It is in the second half of the film that the scale of events opens up for Florya and us. Now the barely glimpsed Germans are appearing in ever increasing numbers from the clasping Russian fog.

Armoured cars, trucks and motorbikes join an ever present spotter plane in the cacophony of mechanised destruction that rips through the silence of the bleak countryside.

Hemmed in by the massing German army Florya becomes part of a village about to be visited by the Nazi hordes. And it is here that the last vestiges of childhood and sanity are seared away from him.

The Nazi’s come with belching smoke and deafening noise.

With cold laughter and indiscriminate gun shot.

With animal lust for murder and pillage.

And they do their worst when they herd the villagers into the barn.

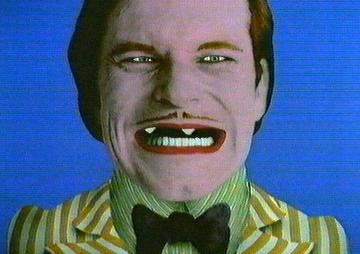

And as we witness one of the most heart shredding, crazed, bludgeoning, blood-lust soaked sequences seen in any war film ever, as this huge, frenzied, Nazi carnival of death carries out it’s sickening work, we see Florya literally age before our very eyes.

We see every single piece of him vanish until there is nothing left but barely restrained madness, as the foul sights and smells of total war etch their deep, permanent mark onto his once young face.

And this sequence must bring up the second real strength of “Come and See” after Elem Klimov himslef…Aleksei Kravchenko.

Supposedly, to help shield him from the more brutal sights, Klimov had the young actor hypnotised. Aleksei Kravchenko has stated that it never actually worked and so he had to pretend, but whatever the reasons it has to be said that he gives one of the most outstanding and harrowing performances from any child actor for decades.

Where are the Oscar Nominations? Where is the international recognition? Nowhere it seems outside of astute critics. And this is a real shame as Kravchenko (and this film) deserve a much wider recognition for the masterful work on show.

You will never forget the close-ups of his startlingly aged face and his haunted, till the day he dies, eyes as he brings home to the audience all the horror that Florya is experiencing.

But Klimov also ensures that his actors have all they need to work with from a visual stand-point.

Tiny details amid chaotic aftermaths of battle and atrocity (dropped weapons, rags, a dead animal here, a discarded helmet there) add to the documentary feel to what we are seeing and the authentic looking (indeed many of them were real) and distressed uniforms on the partisans and the Germans also add an essential realism.

In fact the entire frame in these larger vistas and more complicated sequences is packed with authentic detail, objects and events. And that real bullets were fired during the entire filming shows just how extreme the drive was in Klimov to ensure we see and hear it all as it truly was.

Sound is also expertly utilised to bring home the terrible events unfolding before us, even when they are not shown, like the despairing cries of a young woman as she is hurled into the back of a truck filled with baying soldiers which speeds her away to her fate leaving us only with her screams. And the use of German and Russian songs and classical music is also carefully placed and mixed to add maximum emotional punch to the proceedings,

Klimov ends his film in a way just as startling, unsettling and disturbing as all the more obvious horrors that have preceded it.

With Kravchenko’s war ravaged face staring right at us and Florya’s battered gun pointing at our heads as he unleashed bullet after bullet we are ripped through the terrible legacy that Hitler left the world, we are blasted back to where it all started, blasted back to what Florya has had ripped from him…the child.

And if there is any hope at the end, it is a fragile one. A terribly, horrifically scarred one and one that may just never make it to the end alive.

“Come and See” is a towering work that will remain with you, as it rightly should, and as it did to all those that went through it all for real and survived with whatever part of them was still whole.

Dir: Elem Klimov

Russia, World War II.

A young boy, Florya (Aleksei Kravchenko) joins the local partisan group and thinks he is about to start on a great adventure and save his country from the Nazi invaders.

The reality is very different. The reality is failure, hunger, mud, cold and despair.

The reality is death from afar, death up close and personal, death by laughing, sadistic, swarming hordes, death with no hope of retaliation, death with no end.

The reality is simply…death.

And for Florya death becomes an agonising metamorphosis as everything he was is destroyed, to be replaced with the now stinking, burnt earth of Mother Russia….

Made to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany, the late Elem Klimov’s “Come and See” is perhaps the single most harrowing, bleak and frighteningly realistic portrayal of the true barbarity of all out warfare ever put on screen.

It makes the stupefying dull and self consciously worthy “Schindler’s List” look like the dinner party conversation piece it really is.

Shooting with a jagged, documentary like energy (that never, it must be pointed out, goes into the brain spinning chaos that has become so popular recently) Klimov effortlessly moves us from small scale, intimate moments to extras packed, large scale chaos as he documents the tragic true life events that his fictiona protagonist will lead us through.

Just like the young character we follow, we are never sure just what we are about to come upon, what we are about to witness and how small, large, unimportant or pivotal it may be.

And when added to the stunningly authentic props, costumes and the visual detailing of scenes, we are truly taken on a journey that comes as close to reality as any of us would ever want to get.

Even from the organised chaos of the initial partisan hide-out in the woods, where Florya’s journey truly starts, the young lad is instantly thrown in at the deep end when put on, a very nervous, guard duty.

And not even when he meets a pretty young girl in the camp, Glasha (Olga Mironova), are things as they should be.

Glasha, despite her youth, is obviously already a veteran of the terrible lifestyle the partisans lead and in a wonderful sequence Florya is shocked to discover how close to the surface true madness and black despair lie in the young woman.

He glimpses his future and he does not realise it.

A vicious bombing hurls both the youngsters into the real horror and Florya is soon to witness ever increasing levels of loss and murderous barbarity. Every new horror rips away more and more of the naivety that shielded him from the truth when he first volunteered.

With Glasha leading him (after he is partly deafened by the bomb blasts) Florya does find a brief childlike haven from the horrors as the strange girl dances in the rain for him and together they feel just that bit less vulnerable.

But war is no respecter of respite and Florya will be thrown back into a bedlam worse than he could ever have imagined when they make a return visit to his home village.

And in a gruelling (really gruelling for the two young actors that’s for sure), slow motion sequence we are witness to a manic, despairing Florya tear them both through a filthy, sucking bog as he tries to escape from the truth he cannot face. And we can almost see the child in Florya peeled off layer by layer with each slurping grasp of the stinking mud.

And when a now much hardened Florya (though still hopeful of some kind of victory) sets out with three other partisans to get food he is separated from Glasha and truly plunges head first into a literally soul shredding, mind destroying, inferno.

It is in the second half of the film that the scale of events opens up for Florya and us. Now the barely glimpsed Germans are appearing in ever increasing numbers from the clasping Russian fog.

Armoured cars, trucks and motorbikes join an ever present spotter plane in the cacophony of mechanised destruction that rips through the silence of the bleak countryside.

Hemmed in by the massing German army Florya becomes part of a village about to be visited by the Nazi hordes. And it is here that the last vestiges of childhood and sanity are seared away from him.

The Nazi’s come with belching smoke and deafening noise.

With cold laughter and indiscriminate gun shot.

With animal lust for murder and pillage.

And they do their worst when they herd the villagers into the barn.

And as we witness one of the most heart shredding, crazed, bludgeoning, blood-lust soaked sequences seen in any war film ever, as this huge, frenzied, Nazi carnival of death carries out it’s sickening work, we see Florya literally age before our very eyes.

We see every single piece of him vanish until there is nothing left but barely restrained madness, as the foul sights and smells of total war etch their deep, permanent mark onto his once young face.

And this sequence must bring up the second real strength of “Come and See” after Elem Klimov himslef…Aleksei Kravchenko.

Supposedly, to help shield him from the more brutal sights, Klimov had the young actor hypnotised. Aleksei Kravchenko has stated that it never actually worked and so he had to pretend, but whatever the reasons it has to be said that he gives one of the most outstanding and harrowing performances from any child actor for decades.

Where are the Oscar Nominations? Where is the international recognition? Nowhere it seems outside of astute critics. And this is a real shame as Kravchenko (and this film) deserve a much wider recognition for the masterful work on show.

You will never forget the close-ups of his startlingly aged face and his haunted, till the day he dies, eyes as he brings home to the audience all the horror that Florya is experiencing.

But Klimov also ensures that his actors have all they need to work with from a visual stand-point.

Tiny details amid chaotic aftermaths of battle and atrocity (dropped weapons, rags, a dead animal here, a discarded helmet there) add to the documentary feel to what we are seeing and the authentic looking (indeed many of them were real) and distressed uniforms on the partisans and the Germans also add an essential realism.

In fact the entire frame in these larger vistas and more complicated sequences is packed with authentic detail, objects and events. And that real bullets were fired during the entire filming shows just how extreme the drive was in Klimov to ensure we see and hear it all as it truly was.

Sound is also expertly utilised to bring home the terrible events unfolding before us, even when they are not shown, like the despairing cries of a young woman as she is hurled into the back of a truck filled with baying soldiers which speeds her away to her fate leaving us only with her screams. And the use of German and Russian songs and classical music is also carefully placed and mixed to add maximum emotional punch to the proceedings,

Klimov ends his film in a way just as startling, unsettling and disturbing as all the more obvious horrors that have preceded it.

With Kravchenko’s war ravaged face staring right at us and Florya’s battered gun pointing at our heads as he unleashed bullet after bullet we are ripped through the terrible legacy that Hitler left the world, we are blasted back to where it all started, blasted back to what Florya has had ripped from him…the child.

And if there is any hope at the end, it is a fragile one. A terribly, horrifically scarred one and one that may just never make it to the end alive.

“Come and See” is a towering work that will remain with you, as it rightly should, and as it did to all those that went through it all for real and survived with whatever part of them was still whole.